The Fallen Angle: lessons from a climb gone wrong

Back in October 2016, I was what most UBESters would have thought of as “one of the experienced ones”. I had been involved with UBES for three years and had thrown myself into everything the society had to offer: weekend trips, two Scotlands, four summer trips and had tried to climb at least once a week during term time. I had been Expeditions Officer for a year and was starting another year on the committee as Secretory. Like lots of walk leaders and climbers I had had a few epics and sketchy moments, but always got home with everyone safe and happy, maybe with a new story to torture their concerned parents with.

I was probably regarded as one of the more fearless and/or reckless members of the society. This bit is going to sound arrogant, but I think it’s important to what I’m trying to say, and I’m not trying to present it as a good thing anyway. When talking about the way I scrambled off alone up a crumbling gulley, or soloed the gorge at night with two coiled ropes draped around my neck (probably my stupidest moment, but not definitely), some people would laugh and say I was crazy, some people would pull a slightly forced smile while letting the worry show in their eyes, and very few people would ever say straight up what an idiot I was. I cannot pretend that this reputation didn’t appeal to me. There is a satisfaction in doing things that other people can’t, in proving your (privately self-professed) bravery and adventurousness. And if people were to question me, I had the irrefutable defence that I knew my ability, I knew the risks, and that I was making reasonable decisions based on my experience. After all, who would argue with a member of the committee? That is an attitude to be wary of, whether we see it in others or recognise it within ourselves.

On the day when everything went wrong, I wasn’t doing anything stupid, or even what I would have then considered risky. I was seconding Ben, who had recently learned to lead, up The Arête in the gorge. The route is a classic introduction to multipitch climbing for many UBESters and is a straightforward, if polished, VDiff which I knew well. I thought it would be a good place for Ben to get some experience placing gear and building anchors in a relatively safe environment.

After spending a few minutes at the first belay point, Ben decided to go a bit higher in search of better gear placements and went out of sight beyond the curve of the slab. With the road just behind us we couldn’t hear each other either but there was no cause for concern. Ben gave three tugs on the rope to say he was safe and I put my shoes on and gave three tugs once the rope was tight on my harness. A small amount of rope fell down when I tugged so I waited for it to go tight again, gave another three tugs and began climbing. This was where the near-fatal miscommunication happened. I think either Ben wasn’t sure if he had felt my tugs or he thought I was trying to dislodge the rope from a snag. He may not have yet got a sense of how much rope you expect to pull up as a leader, and rather than putting me on belay, he kept hauling. Down below, I felt the rope tighten each time I stepped up, so I assumed I was on belay and safe.

I will never be sure exactly why I fell. My memory of it has changed several times. I was around the first belay point, twelve metres up. There is no doubt I was being complacent – I did the first few metres without using my hands, taking advantage of being on second on an easy climb. I vaguely remember reaching to flick the rope round to the face of the slab and stumbling backwards. I expected the rope to go tight at any moment. If my initial stumble is hazy, the next second or two is one of the clearest memories I have. I turned to face the ground. For about three steps my feet tried to keep up with the acceleration of my fall down the slab. There was not time for much analysis of the situation. A series of thoughts punched into my head which will stay with me for ever. They were: “I’m falling. Damn. This is what it’s like. This is It. This could be It.”

I landed on my feet, staggered into a boulder and fell to the floor. On impact I had an intense rushing sensation of voiding my bowels, which I took to be myself dying (someone later pointed out that this actually doesn’t happen until after death when your muscles relax). I thought everything would fade to black and that would be that, but instead I started grinding my teeth, writhing and screaming.

A drugged-up hospital selfie

After a while, I calmed down, tried to remember first aid training I had learned with UBES, and started checking myself for damage. My hand came away from my forehead sticky and my trousers were ripped where there was a bloody gouge on my shin, but the main pain was in my back and feet. I didn’t think I had soiled myself, which was a bonus. I didn’t feel too bad. I probably would have tried to stand up if I hadn’t remembered you aren’t supposed to move a suspected back injury.

My phone was undamaged in my pocket, so I called Ash to let him know what had happened and that he would need to help Ben down and then the ambulance (I was briefly flummoxed by the “Do you know the casualty?” question).

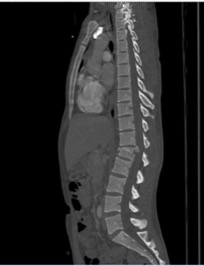

Once everything seemed under control I was in pretty good spirits until after a CT scan a kind nurse told me in a much too trying-to-break-bad-news-gently voice that I had broken my back. He also told me that I had fragments of bone poking into my spinal column and the radiologists looking at the scan couldn’t believe I didn’t have nerve damage. On the flip of a coin, I could have been paralysed. I had never broken a bone before and had perhaps expected some serious bruising or something. Only after I had heard the verdict did I call my parents. Repeating the nurse’s words to my dad was what caused the tears to come. I can’t imagine what it was like for him to tell mum, that her worst fear had come true.

- CT scan showing the crushed vertebra

- Transverse section showing bone fragment poking into spinal column

The repair job

My time in hospital wasn’t great, but I think I had a kind of optimism born out of ignorance regarding the implications of my injuries. When a surgeon came to explain the proposed spinal operation and gave the alternative option of lying still on my back for six weeks, it was a pretty easy choice to make. Much later I learned that before going in for my second operation (as well as my back, I had broken two bones in my left foot, and my right ankle), the surgeon consoled mum by saying “at least this one’s not life-threatening”. In the early days I gave myself hope that this really would be a temporary setback. I saw my recovery in terms of weeks and months, not years.

In a way, my stay in hospital felt like an interesting holiday. There is always something to be said for experiencing a new aspect of life and the fact that I was confined mostly to one room didn’t feel strange because it was part of that experience. It was when I was brought home that my reality became clear. I had lost my independence and was totally reliant on my parents, as if I was an infant again. Lying in bed watching TV and reading all day can be an attractive prospect, but not when it is your prison. If I wanted something as simple as feeling the sun on my face my dad would have to cover me in blankets and wheel me onto the lawn. For a few weeks I had a taste of the life I had so narrowly avoided.

A lot of people remarked on the speed of my recovery and the good spirits I was showing. I didn’t share the sentiments. Everything ground on more slowly than I hoped. Each time I had an appointment with the consultants I would go full of determination that they would see how far I had come and tell me that in the foreseeable future I would no longer be broken. Each time I would come back more disappointed than the last. There is a world of difference between “this should heal up well”, and “you might still have some niggling discomfort.” One means the pain will become a memory, the other means it might be your reality forever. Over a year and a half later, the fall still hurts me every day, just a little.

Before I get to the point, one other thing worth mentioning is that months later I realised I should return the UBES helmet I had borrowed. James handed it back to me saying it was broken. Somehow I hadn’t noticed the large crack on the front at the centre. If I hadn’t worn a helmet for that very straightforward, easy climb, I’d probably be dead.

This has been a very roundabout way of saying that I didn’t truly understand the risks of climbing. I didn’t really know what I stood to lose, or the extent of the pain and anguish I could put myself and my loved ones through. Nor did I understand that the skills I had couldn’t guarantee my safety. That seems obvious when written down but I don’t think it is something people really believe. Most of the skills associated with trad climbing are about doing it safely, which leads to the misconception that if you know all those skills, then it is a safe thing for you to do. That is turn gives a misplaced confidence in your approach, which can be fatal. Every climb, whether you are leading or seconding, needs to be taken seriously.

I want to believe that I have gained some perspective, that this was all a lesson learned in the hardest way and that I can pass it on so that other people don’t have to go through it themselves. I had a lot of time to reflect while not able to do much else. So, some things that are worth saying:

Always wear a helmet. Since my accident, Jono and Catherine also have had incidents where their helmets almost certainly saved their lives. There is just zero reason not to. Often you will see professional or experienced climbers without one, and they are wrong and you can be better than them. Being a better climber doesn’t give you a thicker skull.

Get really good at placing gear, building anchors, belaying, rope skills, and communication, and then try not have to put them to the test. Don’t fall if you can help it. Then all you have to worry about are things falling on you.

Don’t be shy about questioning other people, no matter if they have been climbing longer than you. They should be able to justify their actions and explain why what they are doing is safe. If all they can say is they know the risks, they may well not. Practically nobody in the society is really an experienced climber. The university experience warps your perception. Those who are in charge have often only been doing this kind of thing themselves for only two or three years. In the absence of any real old hands they seem like the pinnacle of knowledge to the newcomers. Remember that in the real world an experienced climber is an actual adult who has climbed for a decade or more and done hundreds or thousands of routes. That is not to say we can’t enjoy our chosen activities in safety, just that to do so sometimes requires the setting aside of overconfidence and a shift in perspective. It is excellent to aspire to be a good climber or mountaineer, but in my opinion that requires the realisation that the best climbers are not the ones that pull off the most daring deeds but the ones which have the greatest understanding of their situation and always make the right decisions, and that is something I believe all of us are

capable of.

The helmet that saved me

Alasdair Robertson